Isolation & New Guinea

How Biogeography Creates Diversity

Isolation is a key component of evolution. The complex geologic history of New Guinea has provided the birds–of–paradise with lots of isolation over millions of years. Combined with intense sexual selection, this has led to the stunning diversity of species we see today.

Isolation and New Guinea

Speciation is the process by which a single species divides into two. A critical ingredient for speciation is isolation. Without it, species can adapt to new conditions, but they can’t divide into new species.

The complex geology of New Guinea has provided the birds-of-paradise with lots of isolating events over the last 20 million years. Combined with intense sexual selection, this has led to the stunning diversity of species we see today.

Range Map

The distribution of a species, or group of species, is called its range. The birds-of-paradise range spans the island of New Guinea, some of the surrounding islands, and sections of eastern Australia.

Of course, species’ ranges are tied to the habitats that they need to survive, but there’s more to it. Range is also linked to the geographic and geological history of the land stretching back many millions of years.

The study of this relationship between biology, geology, and geography is called biogeography.

Origin of New Guinea and Its Birds

New Guinea and the birds-of-paradise have their origins in the continent of Australia. Click the globe to see the origin of the island that would eventually give the birds-of-paradise an isolated realm in which to diversify.

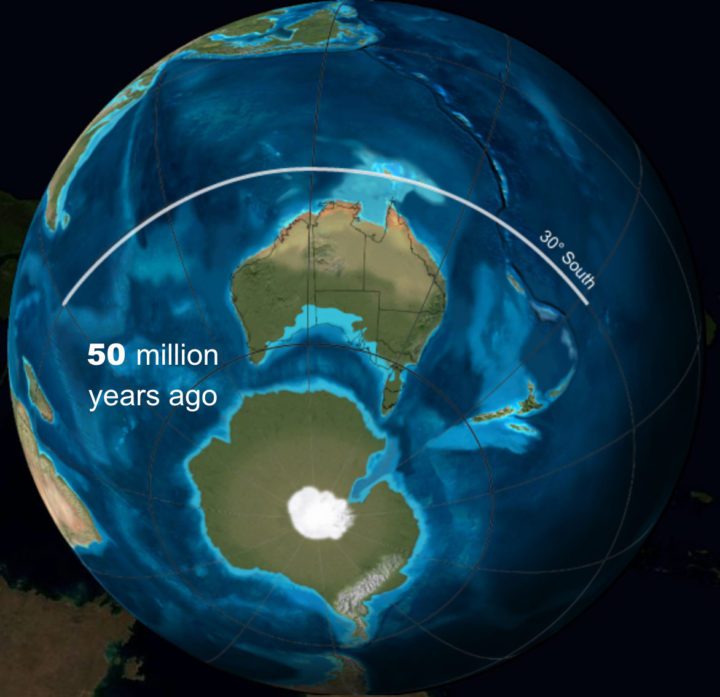

50 Million Years Ago:

The area that will become New Guinea is under a shallow sea on the northern edge of the Australian Plate, far to the south of its present-day position near 5° south latitude.

All dinosaurs, except for birds, are extinct. Despite being so far south, Australia is a warm place, full of an increasingly diverse complement of bird species.

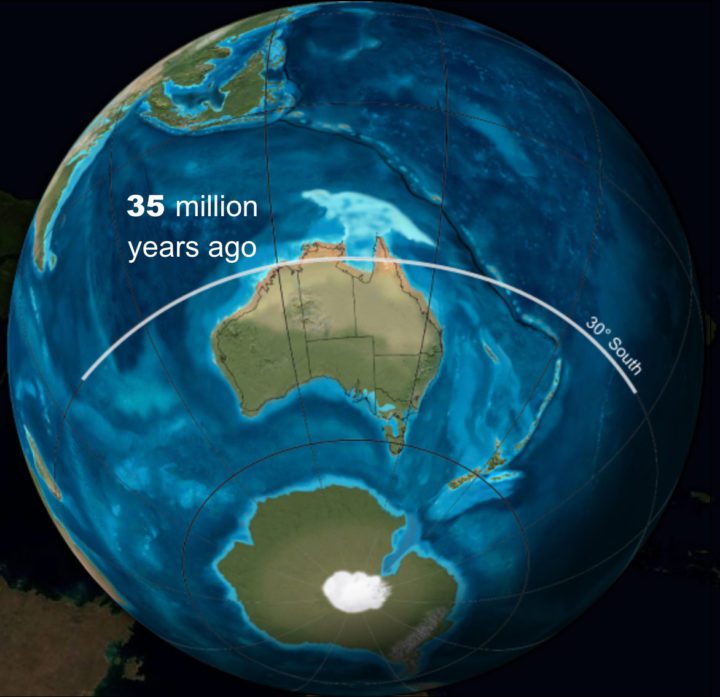

35 Million Years Ago:

Australia has drifted north, passing the 30° south latitude line. The region that will become New Guinea is still underwater, but it has moved into tropical waters.

Australia is full of a wide diversity of bird species including early members of the group that will become crows and the birds-of-paradise

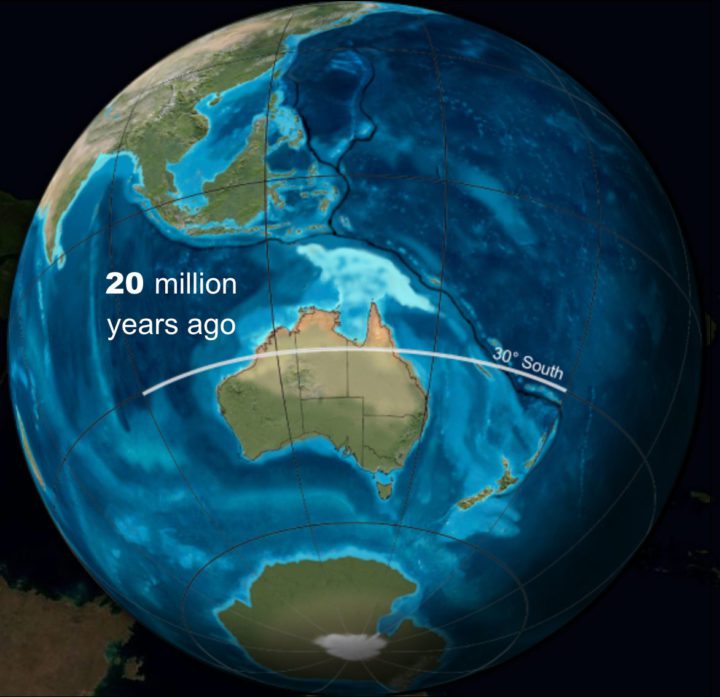

20 Million Years Ago:

Genetic analysis suggests that this is when the birds-of-paradise began to diversify. These early birds-of-paradise were very crowlike, but they had a lot of potential just waiting for the moment when New Guinea would rise out of the sea.

Land Bridges

The birds-of-paradise didn’t have to fly over the ocean to colonize New Guinea. They got there via a land bridge that has repeatedly formed and disappeared as sea levels rose and fell during ice ages. Each time the land bridge disappeared, populations of birds-of-paradise were split into two.

One recent example is the Magnificent Riflebird, which still occurs in both Australia and New Guinea. When sea level rose and covered the bridge about 50,000 years ago, some Magnificent Riflebirds were left on either side. The birds don’t fly across the open water, so these two populations are now evolving separately. Check back in a few hundred thousand years and these populations may have become two new species.

50 thousand years ago

Present Day

Seafloor

Birds-of-paradise, like most nonmigratory birds, don’t venture very far over water. So why are there birds-of-paradise on some nearby islands and not others? Much of the answer lies on the seafloor.

During ice ages, sea levels drop. Shallow waters become land and some islands, like the Aru Islands, are joined with the mainland. Birds-of-paradise have colonized these islands. Nearby, Ceram and the Kai Islands are separated by deep water. Sea level has never fallen enough for them to be connected to New Guinea by land. There are no birds-of-paradise to the west of this line in the seafloor.

It is surprising that an underwater feature would be a barrier for birds, but it is.

Distant Islands

Distance and depth have not kept birds-of-paradise off the islands of the North Moluccas. Both the Paradise-crow and the Standardwing Bird-of-Paradise are found only here. If they didn’t fly over water, how did they get there? The answer has to do with plate tectonics.

Surprisingly, these islands used to be part of the main island. As the Pacific Plate has sheared past the Australian Plate, sections of the earth’s crust have crumbled away, creating islands that spill out into the ocean like slowly rolling boulders. The Moluccas are the oldest of these islands and they have provided a haven for the Paradise-crow, the species on the most ancient branch of the bird-of-paradise family tree.

Narrow Gaps

Sometimes the narrowest of barriers can be enough to keep populations apart and allow them to evolve into separate species. Among the most striking examples of this anywhere in the world is the Sagewin Strait, which forms the boundary between two of the “sickle-tail” birds-of-paradise (in the genus Cicinnurus).

The geologic story of this gap is complicated. A chunk of land was pushed off the end of New Guinea, isolating a population of early sickle-tails. As the new island moved east, this population evolved into a different species. Later as geologic forces broke this island apart, a sliver (now called Batanta) headed back toward the mainland. The remaining gap between Batanta and the mainland is only two miles wide, but it has been enough to keep the species separated. Now, where there used to be one species, we have the Magnificent Bird-of-Paradise on one side, and the Wilson’s Bird-of-Paradise on the other.

Evolution in Isolation

Two evolutionary forces have combined to shape the extraordinary birds–of–paradise.