Feathers

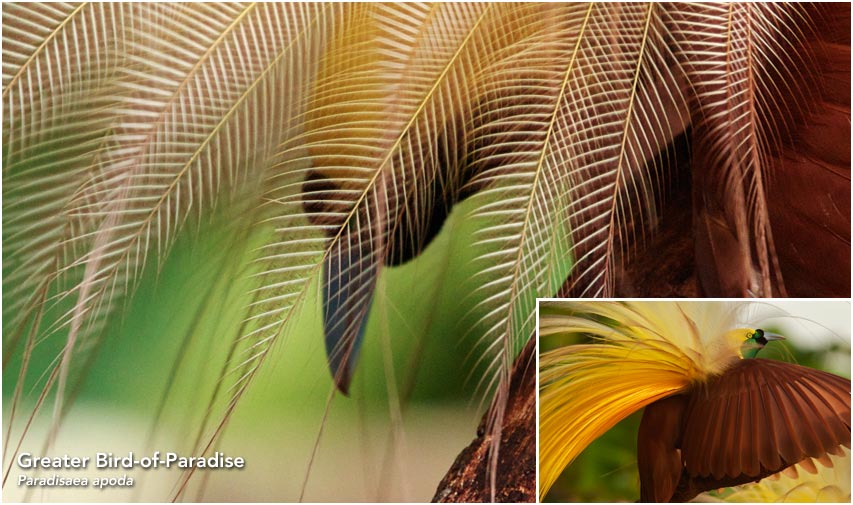

Birds use their feathers for three basic purposes: flight, protection from the elements, and displays. Male birds-of-paradise add to their brilliant colors with specially modified feathers that flutter conspicuously or allow them to transform their shape as they court females. This section explores how these extreme feathers evolved and are put to use in displays.

Feathers: and the Birds-of-Paradise

All birds have most of their body covered with feathers.

And these feathers are important for flight, and for maintaining body temperature, and they’re used for protection from the elements; it’s like putting on a coat or a rain jacket.

All birds also use feathers for some element of coloration that might be – to be more cryptic and camouflaged or to be more conspicuous and colorful.

And in birds-of-paradise, feathers are playing all those same roles but then you have this whole other realm where not only are they colorful, not only are they being used for courtship display but they’re actually modified into something so unfeather-like in many cases that they’re without precedence in all of the rest of bird world.

And that’s really incredible to me that all of these feathers that are so unusual all have their origins back to that same basic feather that we’re familiar with from all those other birds.

Birds-of-paradise, a lot of their feathers have been modified to show off color and shape to the extent that those feathers are hardly useful.

They don’t help with insulation at all, the feathers have a completely different structure.

If you only had those kinds of feathers the bird would probably not survive well if it was cold and wet.

A tail that’s three feet long doesn’t help with flight; it’s like, you know, an airplane pulling along a huge streamer.

It looks cool, it might tell us something like, you know, come to the beach or whatever it might say, but it doesn’t help the plane fly better.

Some birds-of-paradise have feathers that have shapes that when you’re looking at one individual feather it doesn’t really make sense.

But then they put them together with a bunch of other feathers of unusual shapes and create these meta-structures.

We think of it as the shape shifters usually the ones that transform themselves into something very un-birdlike.

And those creations are created with feathers of some sort.

Sometimes they’re feathers of the body, sometimes they’re the wings.

What are the most unusual feathers in the group?

The most unusual feathers in the birds-of-paradise, and they’re some of the most unusual feathers in all of birds, are the ones where what we think of the typical feather structure has been lost.

And what’s happened is that the feather which has a central shaft and all these little smaller branches that come off of it that make the vein of the feather have been fused together so it actually looks like a plastic tab or a piece of plastic.

And that’s what we see on the king-of saxony which has feathers which come off from behind the eye which typically should be, you know, very small, and these have been elongated through the process of sexual selection to being twice as long as the body of the bird and fused so you have this incredible non-feather-like plastic structure.

But that’s not the only instance where you see that fused plastic like structure.

We actually also see it in the tail-wires or tail-ribbons, because they’re more ribbon like, in the red bird-of-paradise which doesn’t have the typical wire that we see in some of the other Paradisaeidaes, but it actually has this long fused plastic curlicue.

They’re very rigid and they hold their shape in a really unusual way, but it’s the same kind of processes that’s gone on with the fusion of the feathers in the king-of-saxony. How does a bird control, if it’s just connected to its skin, where that feather goes and how they move them around their bodies?

All birds have a set of very small muscles that are in the skin of the bird that attach to the base of every feather and can be pushed and pulled on different ways so that the feathers move.

And if you think about a bird that’s fluffing itself up or preening, the bird can move its feathers out away from the body and back down.

So essentially what birds-of-paradise are doing with these really long and very unusual highly modified feathers, is they’re doing the same thing, they’re using the same sets of muscles in the skin and they’re able to move them.

But what’s extraordinary is that they have had some evolution going on under the surface that we can’t see that’s made those muscles much stronger and more robust to give them more degrees of movement than we typically think and also with an incredible amount of precision.

A bird-like that with those incredible precision, long feathers, they don’t have to grow those every year, do they?

All the feathers on the bird are re-grown every year so it doesn’t matter whether they’re just the tiny normal contour feathers or they’re the three-foot long tail feathers on the ribbon-tailed astrapia.

Somehow all those feathers are regrown every year, as improbable as it seems even when you see a bird that’s re-growing them.

It’s hard to believe that it can regenerate something so unusual over the course of the year, and usually it’s only over the course of several months.

So when we think of birds, I think we often think of two things: feathers and flight.

But something the birds of paradise have in their feathers that’s not as common among most birds is how extremely modified these feathers have become to be used as vehicles of carrying color or ornaments that can help change their shape and appearance.

So it’s this kind of gross modification of the feathers for no other purpose than for courtship that really makes the birds-of-paradise stand out among the whole bird world for types of feathers and how they’re used.

End of Transcript

Display feathers are highly evolved versions of a basic feather. They no longer have the standard structure of a central quill and a vane made of tiny interlocking barbs. They’ve evolved into fluffy plumes or stiff wires, some with hard ornaments or tabs. These radical changes, and the muscles that let the bird move them, serve no purpose other than to improve the male’s chances during courtship.

King-of-Saxony: Giant Head Wires

This is a great example of what we think of as a modified feather.

Modified as an ornament for use in courtship display.

We call these two unusual feathers head wires.

They’re definitely unlike any other feathers known to exist.

They’re about twice as long as the body of the bird and they don’t have the normal structure of a typical feather.

Instead of having a central shaft or the rakus, as we call it, with a feather vein on either side, these feathers actually only have structure on one side of the shaft.

They have what appears to be plastic-like tabs running down one side.

And those are actually the fused parts of a normal feather that have been greatly modified here to give this bird this incredible effect.

We don’t see this kind of extreme ornamental feather or this kind of extreme modification in most of the birds.

It sort of makes the male look like he’s got these long antennas.

The head wire emanates from behind each eye and the male can move them around, and in some cases he can push them forward, he can move them to the side.

He can also have them kind of resting, laying across his back.

But on his courtship display territory he really uses these feathers for a maximal effect.

Now it’s important to keep in mind these feathers are almost a burden to carry around.

They actually impose limitations.

Unlike all the other feathers on the bird they aren’t helpful for flight, they don’t do anything for thermal regulation or keeping warm.

They’re evolved for no other purpose than as ornaments used to attract the attention of females as potential mates.

It’s all about their visual presentation.

These feathers really underscore what’s so incredible about the birds-of-paradise.

That sexual selection by female choice can actually shape and influence the evolution of an oddity like the male king-of saxony bird-of-paradise.

End of Transcript

The head wires of the King-of-Saxony are unlike any other feathers in the world. They’ve lost their normal feather structure and become a conspicuously awkward ornament. It may seem difficult to explain the evolution of head wires by the process of natural selection. In fact, they’ve evolved because of sexual selection—an extreme example of female mate choice affecting basic anatomy.

Ribbon-tailed Astrapia: The Three-Foot Tail

The high mountain cloud forests are one of the most magical habitats in all of New Guinea.

So it’s appropriate that these forests would be the home to one of the most magical birds-of-paradise, the ribbon-tailed astrapia.

It really is otherworldly to see.

The ribbon-tailed astrapia gets its name from the tail of the adult males, which is about three times as long as the body of the bird.

This is one of the longest, if not the longest tail lengths relative to body size of any bird in the world.

And yet, as extreme as they are, these are still feathers like any other feathers on the bird.

And every year an adult male astrapia will lose those two feathers of his tail during molt and have to re-grow the whole entire thing.

One of the things I love most about the ribbon-tailed astrapia is how its extremely long tail has really come to defy everything that we think about the role of feathers on birds.

Typically we associate feathers with basic function of survival in birds – aiding in flight, keeping warm, keeping birds dry – and yet these feathers defy all those things.

Here you have this three foot long tail that hinders flight, clearly does nothing for keeping warm, and it often gets in the way when the bird is trying to forage.

And it’s at these times, when you see the male fly with a struggling undulations flight or with his tail wrapped around a branch while he’s trying to forage, that you can really come to understand that this is an adaptation produced by sexual selection and not the product of natural selection adding to some survival advantage.

End of Transcript

The tremendously long tails of male Ribbon-tailed Astrapias don’t help them survive, in fact, they get in the way. Males sometimes have to pause to untangle their tails before they can fly away—not a survival advantage. But the tails do help them attract females. And by carefully choosing their mates, the females determine which males’ genes—and what kinds of tails—survive to the next generation.

Feather Gallery